FROM THE CANADIAN OPERA COMPANY’S

ISSUE 3 of NOTES

A Conversation with

SOPRANO MIRIAM KHALIL

As part of their work in the COC’s Company-in-Residence program, Against the Grain Theatre has been developing a new opera. BOUND takes Handel arias and ensembles, reconstructs them through a new interpretation by composer Kevin Lau, and layers the music against new English-language texts drawn from real-life world events. In the leadup to tonight’s opening, we asked Founding AtG member and Ensemble Studio graduate Miriam Khalil to share her thoughts on the challenging process of creating art that responds to contemporary realities of persecution, oppression, and asylum.

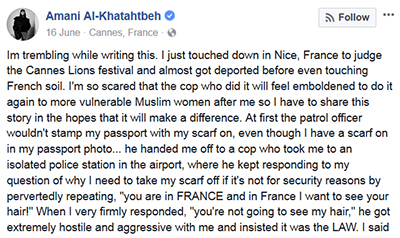

n BOUND each artist’s performance is informed by a real-life story in the news. What’s the background of the character you portray?

My character is based in part on Amani Al-Khatahtbeh, a Muslim-American journalist who was detained upon her arrival at an airport in France and forced to remove her hijab under threat of deportation.

How are the singers being tasked with developing these characters?

The past couple of weeks have been spent in challenging discussions about the real-life stories that serve as the launching pad for our characters, but we’ve also been bringing them out of the documentary realm into interpretation and characterization. It is a true collective endeavour, in that all of us are researching our characters deeply and then bringing that back to the rest of the creative team for continued exchange and collaborative dialogue. It’s a powerful process that builds a kind of shared reserve of empathy and nuance that we can draw on to get closer to these realities.

I understand you’ve also been having lots of conversations with subject matter experts in refugee and immigration law, trans rights, and marginalized and underrepresented people as part of the project. What’s that been like?

Alia Rosenstock, a Toronto-based immigration and refugee lawyer, explained the basics of Canada’s refugee system. We learned about some aspects of a refugee’s experience that we wouldn’t ordinarily encounter, including the hardships people are willing to endure to escape to Canada and some of the obstacles they face upon arrival.

Many refugees are illegally detained and tortured in their countries of origin, only to be detained again, once they’ve arrived in countries where they’re seeking asylum, including the USA and Canada.

Some are detained for long stretches of time, while their files are being processed. The effects of long-term detention can be devastating to an individual’s mental health and on the family members who rely on them, including children.

With Rania Younes, a representative from the Canadian Arab Institute, we talked about the hijab, women’s rights in Canada, and Islam. For her personally, wearing the hijab remains a form of self-empowerment.

But there are also prejudices that affect so many aspects of daily life for a hijab-wearing woman in today’s political climate, from obstacles to full participation in the public sector, to feelings of invisibility to being treated with hostility.

Of course we could only absorb a small amount of what she goes through, but it was sobering to begin understanding what it takes simply to practice the freedom that our country guarantees.

I’m really in awe of each and every one of our special guests for their openness, generosity, and curiosity. For my colleagues and me this whole project is about much more than just an opera production—it’s about an expanding scope for empathy and inclusion that we can carry with us as artists and human beings.

Your family immigrated to Canada in the 1990s. The lived experience of people of colour in this country is often at odds with the way Canada likes to present itself as an almost utopian post-national state. What was your experience growing up here?

My immigration to Canada was mostly positive. I was bullied for a time, but I don’t know if that had anything to do with race. I attended a small school and I was the new girl that didn’t speak the language (my first language was Arabic).

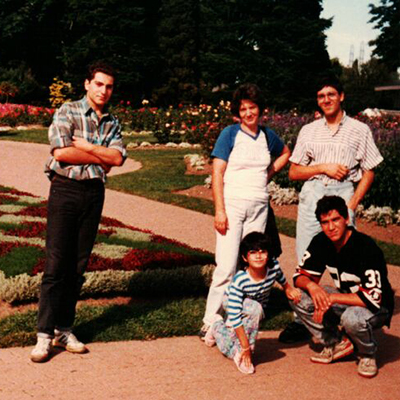

My parents and older brothers had much bigger struggles and were much more alert to the pressures of assimilation. My father worked odd jobs for the first year and eventually bought a restaurant (Italian, of course), where he and my brothers worked until my father’s retirement. My brothers each pursued their own career path while helping at the restaurant and are all business owners now.

My parents worked really hard to build a life for us in Canada. My mother was a stay-at-home mom in Damascus, but when we moved to Canada she learned English, learned how to drive, and took Early Childhood Education courses. She became a licensed caregiver and eventually ran a home daycare after years of working in the Ottawa School Board.

First summer in Ottawa: Miriam’s mother Taghrid (standing in the middle) surrounded by her children Nabil and Wassim (also standing) and Miriam and Maher (crouching in front). Photo courtesy of Miriam Khalil.

In a big way, we were very lucky because we had family in Ottawa and there is a large Lebanese/Arab community that welcomed us from the beginning. I remember being amazed at the amount of family we finally had in one place.

Tell me about the Handel aria you sing.

“Ah! mio cor, schernito sei,” from Alcina.

It has an introduction of dissonant chords finding resolution and clashing again in a heartbeat-like pulse. It’s very contemporary sounding for its time and is really quite moving.

The B section moves faster and suggests a growing strength, as the character moves to anger and determination, collapsing again into the A section which restates its emotions quite beautifully to find resolution in a tone of sadness.

Music Director Topher Mokrzewski in rehearsal with Miriam Khalil for AtG’s BOUND, photo Darryl Block

Why is a Baroque composer like Handel being used to tell these stories?

Handel’s music covers such a wide range of emotions and is so beautiful in its purity. His music breathes and can seem bare at times, which makes it so vulnerable and human and so apt in exploring the emotional journeys of the oppressed.

And then composer Kevin Lau—who has been with us since day one, immersed in our conversations, etc.—will actually orchestrate and manipulate Handel’s music with electronic amplification to create new juxtapositions for future workshops.

“At a time when the world seems to be spinning away from hope and unity, BOUND will look to moments of beauty, acceptance, and diversity.” —AtG Director Joel Ivany. Photo Darryl Block.

What happens when you bring Baroque music into contact with stories that have a contemporary sense of cultural and political urgency?

Most of Handel’s operas deal with the big themes: war, love, hate, and death. Baroque music can be incredibly moving because it takes on these essential concerns with emotional honesty and musical simplicity. Within that basic vocabulary, however, Handel develops these intricate relationships with dissonance and resolution, which pull the music forward into emotional waves and gestures that seem perfectly matched for our own political and cultural upheavals.

What role does art play in the age of Trumpism?

That’s one of the big discussions we’ve been having throughout the rehearsal process: “Can art really make a difference?” I don’t have an answer to that.

I can say that this week has been incredibly transformative for me. We talked about issues related to the Travel Ban on Muslim countries, human rights violations, our right to privacy, and the freedom to wear what we want. As artists I think we’re all so fortunate to be in a creative community in which we can take a week to discuss and debate the injustice that we see on our newsfeeds and meaningfully apply those conversations, those breakthrough moments, to our work.

The depth of these discussions has left me restless and curious.

In the age of Trumpism, it is so easy to feel helpless and voiceless. The blatant disregard of a very specific set of individuals and the lack of care for their well-being is disheartening. However, in discussion with these open-hearted artists, I find myself hopeful and excited by what art can do to create change in our times.

We have it in us to create a higher sense of awareness of the bigger issues and to lay down a foundation of empathy for “the other.”

Miriam Khalil is a Lebanese-Canadian soprano performing in Against the Grain Theatre’s Handel mash-up BOUND, running December 14–16 at the COC’s Culture Hub, 227 Front St. E. in Toronto. Rush tickets ($35 cash only) are available at the door for each performance. Thank you to the Canadian Opera Company and Nikita Gourski for sharing this Issue of NOTES. AtG is proud to be the inaugural Company-in-Residence of the Canadian Opera Company.